PART 7.1

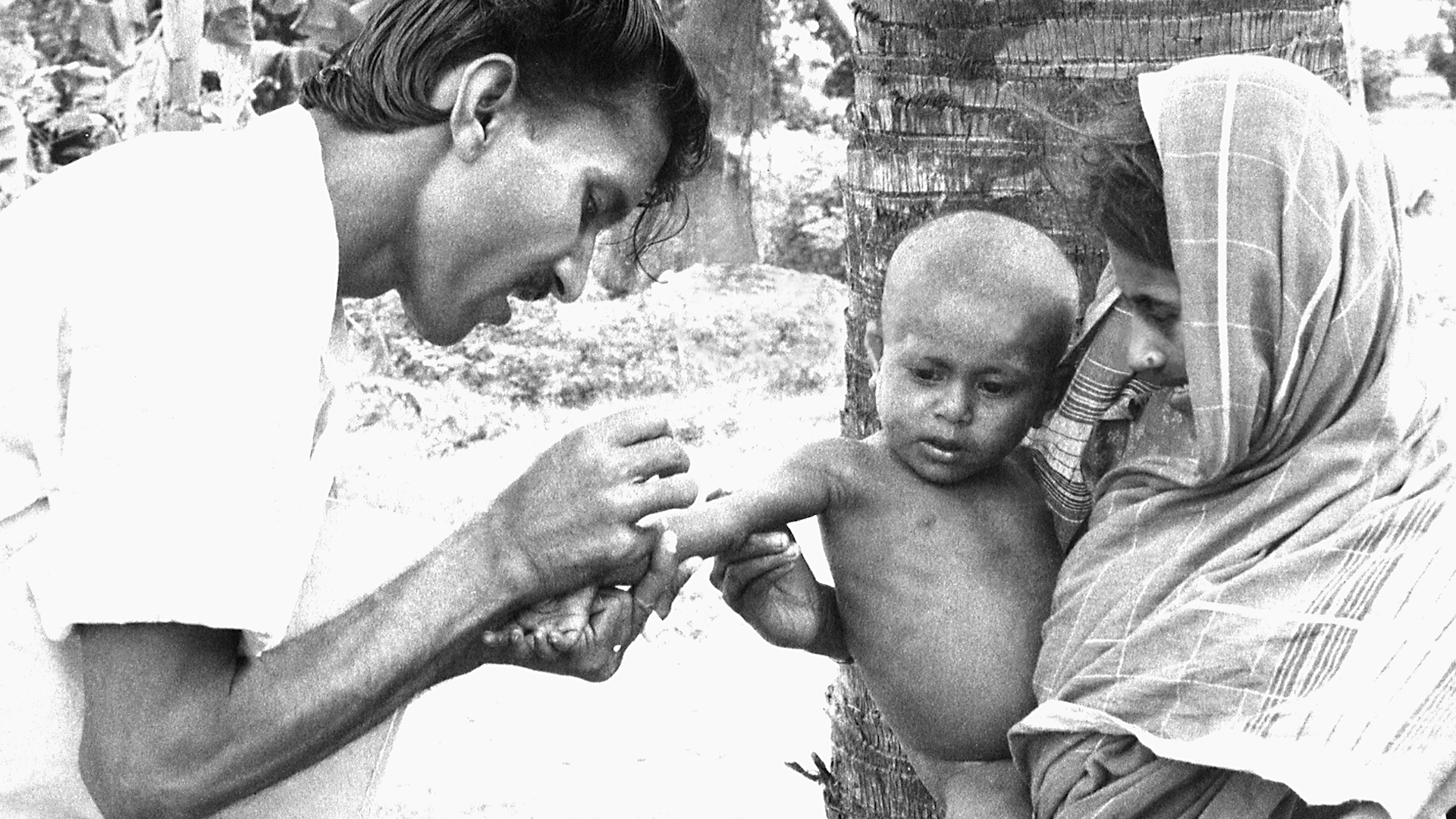

In early 1974, smallpox outbreaks were appearing in areas of India that had been smallpox-free for months. After a week of plotting the epidemic with pushpins on hand-drawn maps, a pattern emerged. Each outbreak began with a working-age young man who had returned home to his village. These cases were “importations.” The young men had come from—or traveled through—the bordering state of Bihar. Cases were originating in Tatanagar, the company town of the corporate behemoth, Tata Companies. Tatanagar, a city in the state of Bihar, had no centralized government, and no public health structure in place.

PART 8.1

In 1973 India had thousands of cases of smallpox. For a while they were reporting one thousand new cases every day. Leaders of the eradication effort wanted to solicit help from WHO and bring in physicians, epidemiologists and health worker volunteers from other countries to supplement the Indian teams. But the Minister of Health for India felt that India had plenty of health workers and volunteers to do the job and said that people from other countries were not needed. The Minister's support for the smallpox effort was essential, so the team had to convince him to support bringing in workers from other countries without being critical of the great resources India already had.

PART 9.2

Partners in Health (PIH) is a non-profit global health organization established by Paul Farmer, Jim Kim, and three colleagues to bring health care to the poorest people in low-income countries. PIH believed that these people deserve healthcare that was as good as the healthcare that rich people in the most advanced countries received. They found that poor people living in a shanty town outside of Lima, Peru had very high rates of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDRTB), a disease that was notoriously hard to treat.

PART 9.3

There are medicines that could save the lives of the 500,000 children who die from malaria each year. Most of these children live in the low-income countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. Novartis manufactures the drug, artemisinin-based combination therapy, that is the standard of care for the treatment of P. falciparum malaria, the most deadly form of the disease. Although the global health community has for a long time been skeptical and wary of the private sector where profit was the driving force, Novartis happened to have a CEO who came from the field of global health and was inspired by the vision of global health equity. But neither these malaria-endemic countries nor WHO could afford to purchase commercially the amounts of this drug needed to treat the children who were at risk.